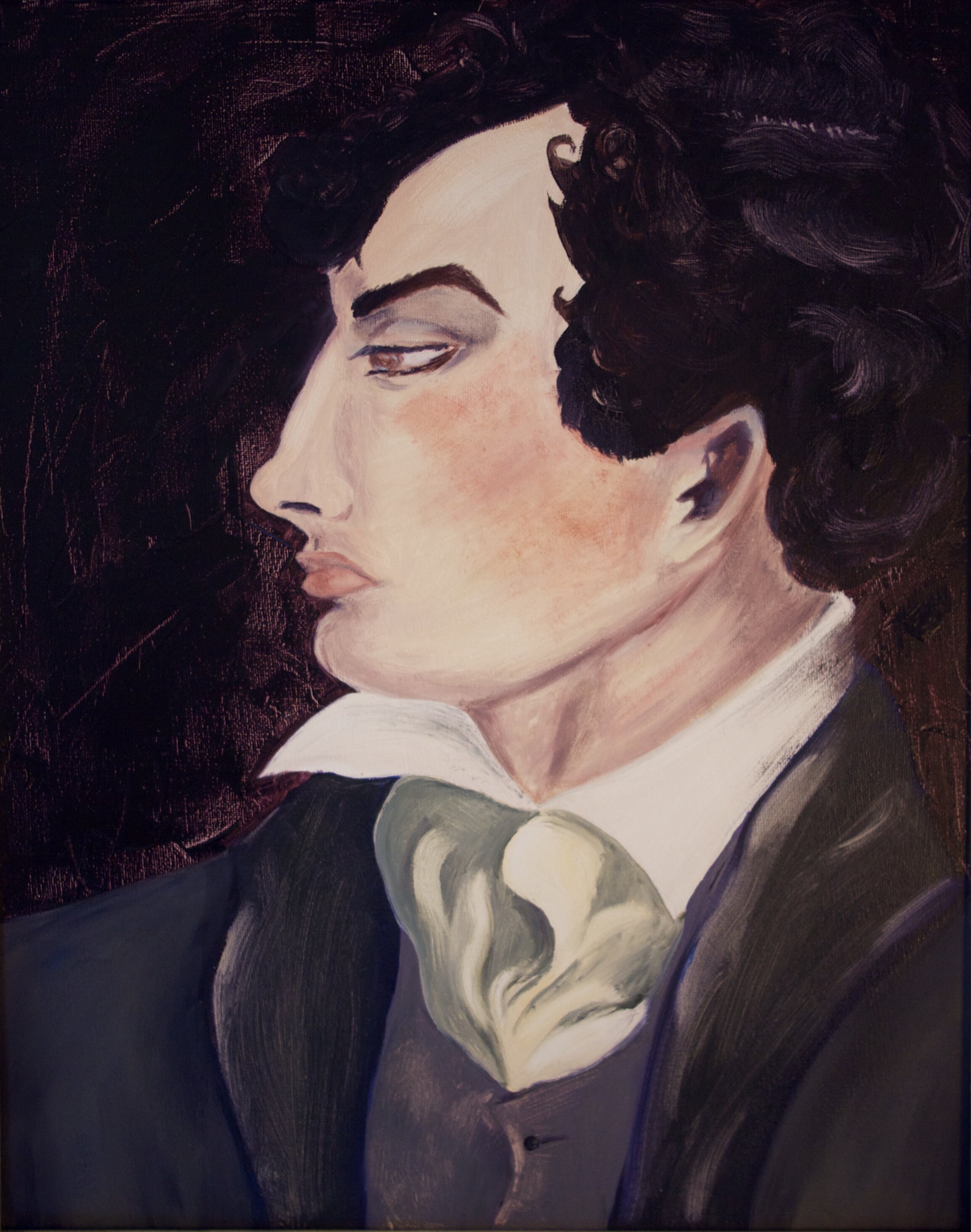

Lord Byron

Man’s a phenomenon, one knows not what,

And wonderful beyond all wondrous measure.

‘Tis pity though in this sublime world that

Pleasure’s a sin and sometimes sin’s a pleasure.

Few mortals know what end they would be at,

But whether glory, power or love or treasure,

The path is through perplexing ways, and when

The goal is gained, we die you know –– and then?

What then? I do not know, no more do you,

And so good night. . . .

(Don Juan, Canto I. st 133-4)

In 2007, I was introduced to Lord Byron. It is ironic, in fact, that I hadn’t heard of him before, as the texts and films that inspired me as a child stemmed out of the vast universe of his influence (there was a reason David Bowie was my first idol).

One day, when I was a young adult in a mandatory Survey of English Literature class at Umpqua Community College, I read Byron . . . and Wordsworth, and Coleridge, and Shelley, and Keats . . . and I felt like I had heard myself for the first time. I had read a poem and learned about a poet who made me both sound less insane to myself and made me appreciate––truly for the first time––the power of the written word. I promptly walked down with my professor after class and became an English major.

Upon reflection and years of working on Byron, of course, the attraction seems not surprising at all. Even my rampant very young self desiring an interlocutor with whom I could exchange letters makes more sense now . . . my intense desire to hear myself better through an exchange with a likeminded person (of course, there were none, so thank you mom for driving me to the post office so I could send letters to myself for years. Oh! the idiotic joy of going back to the post office to find you had received some sort of correspondence).

It is through Byron’s theories of artistic productive flow–––and overflow––and tracing the maturations of his deep revelations of a self awareness stemming from (or leading to) a state of overwhelming tension, that I first found selfhood and artistic identity beautiful. In that beauty, as well, I found that artistic production and self-conscious theorization assisted in my own mental marking: to see and accept the impossibility of resolve and to make art because of that.

With Byron, we have a continual search for moments of both connection and consumption––of bondage and release––of death and escape. And for him, while rhyme may not completely “anticipate” madness or keep it at bay, it is helpful as a tool for looking towards other spaces that lie beyond the confines of our own perceptions. To imagine what the absolute freedom and expanse of Darkness may feel like, for instance. To imagine the self utterly consumed and eliminated. Yet, in our imagining accept our limitations as beings in the present, which makes our endless searches all the more interesting.

Or, in the words of Blanchot “it is dark disaster that brings the light”